AI promises a huge transformation, but do not ignore the fallout

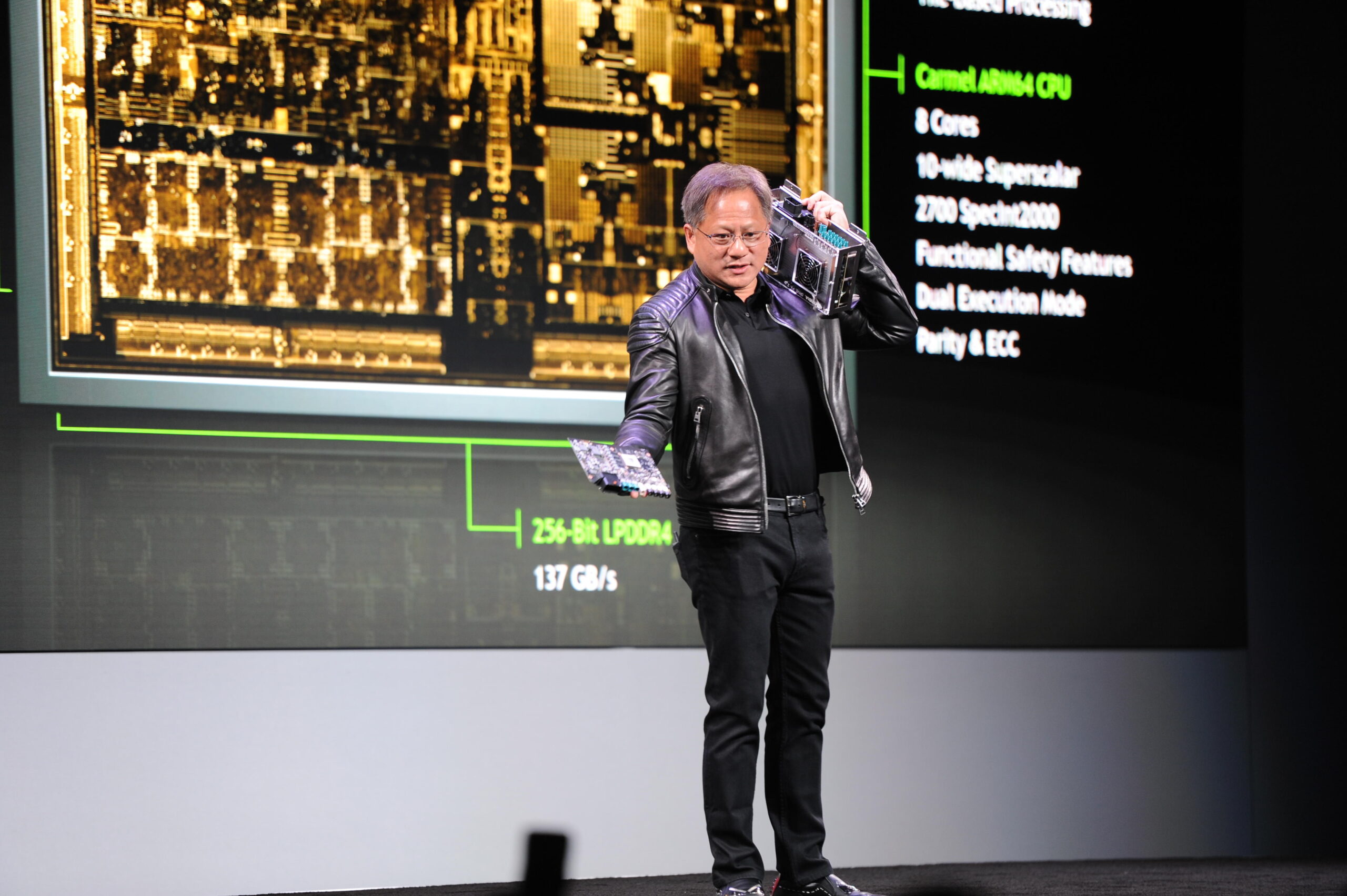

Artificial intelligence is at the very forefront of investors’ minds, and with good reason. AI made a significant contribution to Microsoft’s record $62 billion earnings in the fourth quarter of 2023, a performance that pushed the stock market value of the company above $3 trillion for the first time and approaching the size of the entire British economy. Nvidia, arguably the most-hyped stock in 25 years, is up by more than 350 per cent over the past 12 months and is now the third largest company on the US stock market. It is estimated to produce four out of five of the chips needed to run advanced AI systems.

Suddenly AI is at the heart of every consultancy presentation. Chief executives rarely make it through interviews without name-checking AI. The technology has economists excited, too, in their case at the prospect of an upturn in productivity growth as it transforms the knowledge and information management economy and as it parks its tanks firmly on the lawn of a whole range of creative industries. It remains to be seen whether generative AI, widely seen as being the biggest digital breakthrough since the internet, has as many functional applications as claimed, but right now there are trillions of dollars being staked that it will.

Politicians past and present are catching on, and not simply because Rishi Sunak might be lining up his next job. He and Jeremy Hunt, and their respective shadows on the Labour benches, are acutely aware that the widespread use of AI in the delivery of public services is crucial if demographics and stubbornly low public sector productivity are not going to result in a remorselessly higher rate of UK tax. This tax rate is already on track to reach an 80-year high.

From the processing of citizen enquiries to smarter defence procurement to healthcare diagnostics, there is huge potential for AI to enable the state to do more with less. There will be as-yet-unimagined uses. Last year Tony Blair, the former prime minister, and William Hague, his one-time opposite number, released a report on the economic opportunities for Britain from being a global leader in AI. While not underestimating the challenges such leadership will require, they are almost certainly on the right side of history.

So far, so encouraging, and, notwithstanding what I am about to say, AI is almost certainly a tool that will enable human activity to be more efficient, something that in a resource-scarce world has to be good news. Yet this enthusiasm should not lead economies to sleepwalk into some of the challenging implications of AI adoption. There are people much better-qualified than I to opine on the threats to stable politics and contented societies from deep-fake imagery, viral digital content and identity theft, all of which are being turbocharged by generative AI. However economists, sticking to their running lane, should be mindful of the twin-sided impacts that AI will have on a services-heavy economy that at present creates 80 per cent of British wealth and jobs.

To illustrate this, one needs to see AI’s potential impact as analogous to the globalisation of the manufacturing sector in recent decades. This, and the concurrent rise of China, had a huge impact on industrial sectors in western economies. Globalisation removed the power of localised manufacturing monopolies, in turn removing wage-bargaining power from workers and communities. Rather than competing with geographically proximate companies in Cambridgeshire, a widget maker in Wisbech was going toe-to-toe with one in Wuhan. It was little surprise that salary differences, among other cost differentials, meant demand ebbed away from western workers and moved east. The impact on community cohesion, waning support for mainstream economic policy and the politics of Donald Trump and Brexit can all be traced back to this de-industrialisation of western economies. Has AI the potential to unleash a second such wave of disruption? There must be a reasonable chance.

At this point, mainstream economists correctly will note that overall welfare is unambiguously enhanced by trade. Trade brings greater choice for consumers, incentives to innovate and bears down on inflation. AI-enabled trade in services looks set to be a tantalising example of history rhyming, if not repeating. Trade in services is at present only 14 per cent of global GDP, while trade in manufactured goods is more than 50 per cent. The transition of trade-light sectors such as professional services, creative services and knowledge management — to greater trade density — will unfurl similarly disruptive economic impacts.

Is this an excuse to introduce trade barriers either in the form of cross-border tariffs, differentiated professional accreditation or divergent licensing standards? I suggest there will be intense pressure from workers in sectors affected by AI to introduce just such barriers to trade. This economic debate is centuries old and AI looks poised to be the latest frontier.

It is unlikely to be the technology that unleashes mass unemployment. Like its disruptive forebears, it will change, destroy and create jobs. What will be interesting is whether politicians bruised by the recent backlash to globalisation are dissuaded from throwing their economies headlong into the AI revolution.

Britain’s AI safety summit last year at Bletchley Park focused, sensibly, on guide rails, standards and regulation, all of which are necessary to foster this emergent technology. This is particularly the case with generative AI, which takes existing creative material as its source material for new, repackaged content. We can see already players in the commercial world of media, gaming, art and literature positioning their legal teams to challenge this unfettered use of proprietary content. This is the latest module of a long-running dispute between content creators and technology firms. The line between protecting proprietary content and economic protectionism won’t be black or white. It will be multiple shades of grey. It is one of the reasons why advisory groups and lawyers are licking their lips at the enormous fees that will be thrown off from arguing this interface.

For modern economies, largely struggling with productivity growth for the past two decades, AI has enormous potential to break this trend and to address many long-term problems. But the inevitable losers from this transformation will not go quietly into the night. Governments need a plan to deal with the fallout.

Simon French is chief economist and head of research at Panmure Gordon

Post Comment